︎

Guaranteed by the Constitution?

“We...appeal for an equal chance in the race of life in this our adopted home--a large number of us have spent almost all our lives in this country and claim no other but this as ours. Our motto is: ‘Character and fitness should be the requirement of all who are desirous of becoming citizens of the American Republic.”

Wong Chin Foo, 1893Still Left Out

︎

The 15th Amendment advanced the right to vote in America and made voting rights a concern of the Federal government. But states controlling suffrage qualifications found ways to continue to deny the right to vote.

On the Federal level, denying citizenship to some groups, by default, denied them the right to vote.

In 1882 Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act that not only barred immigration from China but also prevented Chinese people in America from becoming naturalized citizens.

The 14th Amendment had excluded from citizenship Native Americans not “under the jurisdiction” of the country. Yet, while Indian reservations qualified as being “in jurisdiction,” the U.S. government did not press for voting rights on those reservations.

(Above) Cartoonist Thomas Nast creates sympathy for Native Americans who could not vote. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

(Left) Cartoonist Thomas Nast lampoons Senators who called voting rights a path to “civilization,” but who denied it to Native Americans. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

A political cartoon that lamented the Chinese Exclusion Act. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

“How can any one who is able to use reason, and who believes in dealing out justice to all God’s creatures, think it is right to withhold from one-half the human race rights and privileges freely accorded to the other half, which is neither more deserving nor more capable of exercising them?”

Mary Church Terrell, 1915.19th Amendment

︎The right of American women to vote took a longer and more difficult route to a Constitutional amendment.

The first call for votes for women (after they had been disenfranchised by states in early America) came at the 1848 Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York. The women there worked hand-in-hand with the abolitionist movement and fully expected to receive Constitutional affirmation of their right to vote along with the 14th and 15th Amendments.

Congress disappointed them.

The first call for votes for women (after they had been disenfranchised by states in early America) came at the 1848 Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York. The women there worked hand-in-hand with the abolitionist movement and fully expected to receive Constitutional affirmation of their right to vote along with the 14th and 15th Amendments.

Congress disappointed them.

But women reorganized and embarked on a fifty-year, multifaceted campaign to advance female voting rights in America.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the National Woman Suffrage Association supported the first amendment proposal fielded by Congress in 1878. Congress voted it down.

Lucy Stone and the American Woman Suffrage Association pursued voting rights on the state level. They were successful: several states west of the Mississippi (including Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, and Idaho) granted women the right to vote before the 20th Century.

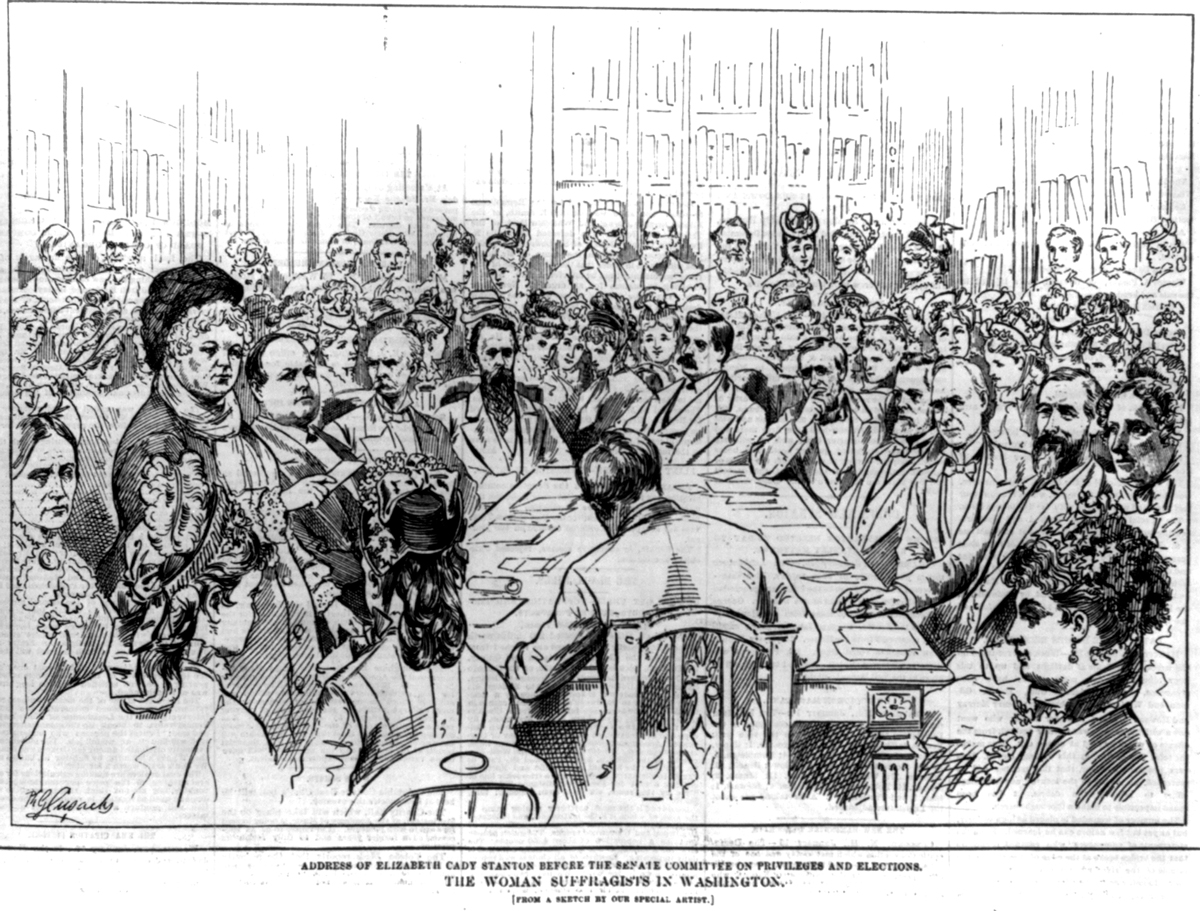

(Above) Women’s suffrage activists petition a Congressional committee in the 1880s. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Lucy Stone and the American Woman Suffrage Association pursued voting rights on the state level. They were successful: several states west of the Mississippi (including Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, and Idaho) granted women the right to vote before the 20th Century.

(Above) Women’s suffrage activists petition a Congressional committee in the 1880s. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Mary Church Terrell. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Mary Church Terrell. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The largest women’s suffrage organizations had a contentious relationship with Black women who also pushed for the right to vote. Still, the American Equal Rights Association, and later, the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) became firm advocates for voting rights.

When asked what Black women could do with the vote, activist Nannie Helen Burroughs replied, “What can she do without it?”

NACW president Mary Church Terrell pushed for radical activist Alice Paul to include Black women in her advocacy. She rallied her own organization, saying “nothing could be more inconsistent than that colored people should use their influence against granting the ballot to women, if they believe that colored men should enjoy this right which citizenship confers.”

Near the end of World War I, after American women rallied to the war effort, President Woodrow Wilson signaled his support for a Women’s suffrage amendment. It passed congress in 1919, and states ratified it in 1920.

The 19th Amendment guaranteed a Constitutional right to vote for 26 million women.

Still, Black women remained effectively disenfranchised by state constitutions that already marginalized Black voting for men.

When asked what Black women could do with the vote, activist Nannie Helen Burroughs replied, “What can she do without it?”

NACW president Mary Church Terrell pushed for radical activist Alice Paul to include Black women in her advocacy. She rallied her own organization, saying “nothing could be more inconsistent than that colored people should use their influence against granting the ballot to women, if they believe that colored men should enjoy this right which citizenship confers.”

Near the end of World War I, after American women rallied to the war effort, President Woodrow Wilson signaled his support for a Women’s suffrage amendment. It passed congress in 1919, and states ratified it in 1920.

The 19th Amendment guaranteed a Constitutional right to vote for 26 million women.

Still, Black women remained effectively disenfranchised by state constitutions that already marginalized Black voting for men.