︎

A Revolution?

“If we fight to maintain a republican government, we want republican privileges… All we ask is the proper enjoyment of the rights of citizenship.”

A soldier in the 54th Massachusetts.Ballots for Bullets

︎

In an 1864 speech Frederick Douglass demanded not only the end of slavery, but also the elevation of Black men to citizenship with the right to vote. Few White Americans agreed with the aspiration, but the process of emancipation already underway had unleashed a great reconsideration of who counted as an American.

The Emancipation Proclamation permitted the United States to enlist Black men in the army. At least 198,000 eventually served in the Army and Navy. Since serving in the nation’s military had long been considered a privilege of American citizens, Black soldiers claimed their service entitled them to the rights of American citizens as well.

Still, the Emancipation Proclamation’s assault on slavery and the practical destruction of the institution at the hands of the United States Army and enslaved people themselves did not mean Black men and women automatically became citizens at the end of the Civil War.

(Above) Political cartoonist Thomas Nast calls attention to the quick pardon of former Confederates and the still-outstanding question of the status of freedpeople, including United States Army veterans, in August, 1865. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

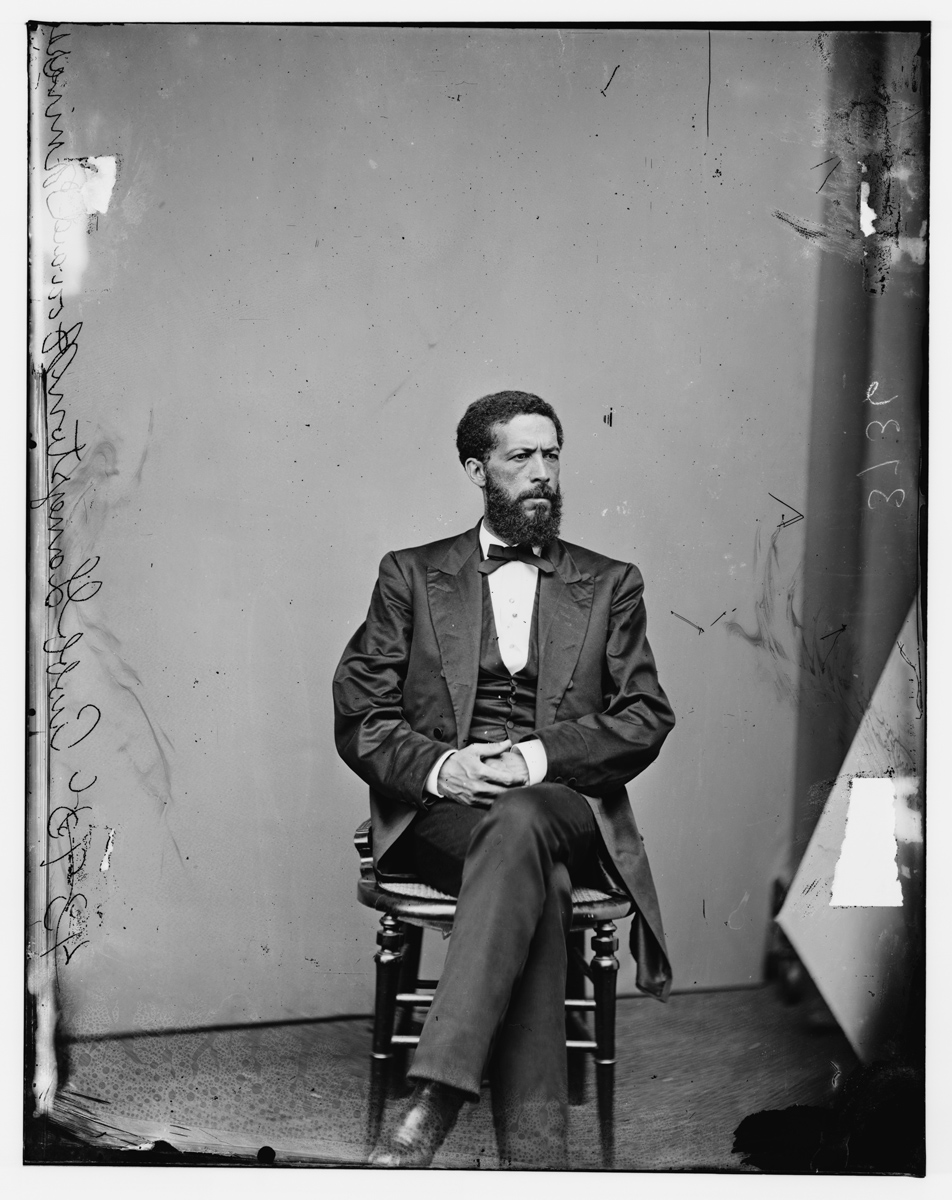

(Left) Frederick Douglass. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

(Left) Frederick Douglass. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Do Citizens Get the Right to Vote?

︎

“Without the right to share in the governing power, no man is really free.”

Congressman George W. Julian of Indiana, 1866.

This broadside celebrates emancipation. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The 13th Amendment ended slavery. It implied citizenship for the formerly enslaved, but did not explicitly grant it. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 did so. But civil rights still did not equal political rights, including the right to vote.

Even though a growing body of Federal legislation during Reconstruction gradually expanded civil rights, it never did the same for political rights.

Black Americans protested. The National Equal Rights League, formed in 1865, pressed for an articulation of citizenship rights for Black Americans, including the right to vote. In 1868, the 14th Amendment was the first to mention “the right to vote,” and this legislation put Federal authority above states in matters of citizenship and civil rights.

Even though a growing body of Federal legislation during Reconstruction gradually expanded civil rights, it never did the same for political rights.

Black Americans protested. The National Equal Rights League, formed in 1865, pressed for an articulation of citizenship rights for Black Americans, including the right to vote. In 1868, the 14th Amendment was the first to mention “the right to vote,” and this legislation put Federal authority above states in matters of citizenship and civil rights.

Through confirmation of birthright citizenship and the Privileges and Immunities, Due Process, and Equal Protection clauses, the Amendment stated that states could not abridge the rights then enumerated in the Constitution of any person in the United States.

But up to that point, the right to vote did not appear in the Constitution.

The 14th Amendment left out women’s suffrage over the objections of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Susan B. Anthony, and the American Equal Rights Association. It also excluded American Indians from the protections of citizenship.

But up to that point, the right to vote did not appear in the Constitution.

The 14th Amendment left out women’s suffrage over the objections of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Susan B. Anthony, and the American Equal Rights Association. It also excluded American Indians from the protections of citizenship.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone, and others signed this petition calling for voting rights for women during the post-war debates over expanding suffrage. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration.